|

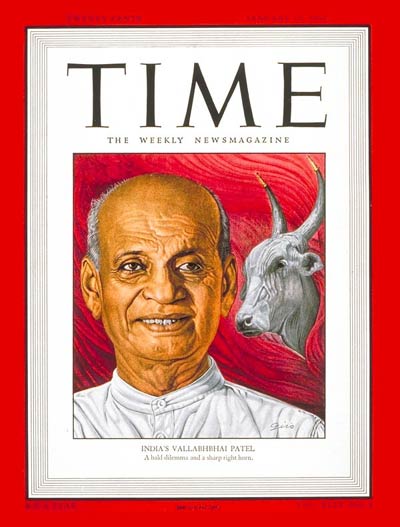

Extracts from TIME Cover Story

January 27, 1947

Princes and Paupers. On the 17th anniversary of the Indian Congress’ Purna

Swaraj (complete independence) resolution of Jan. 26, 1930, India was

almost completely free of Britain but in danger of lapsing into anarchy.

The infant country faced these problems, among others:

· Hatred between

the Hindu and Moslem communities, which flared last August into the Great

Calcutta Killing when 6,000 died, has now hardened into a grim struggle

over Pakistan.

· Rising prices and falling production have intensified

the conflict between millions of the poorest and some of the richest people

in the world. Strikes are bubbling all over India. Communist power is

rising. The Congress Party is likely to split into right and left groups

and the Moslems face a similar division.

· While Gandhi continues to

attack industrialization, some of his most devoted followers go ahead with

plans to make India the industrial heart of Asia.

· Freedom for India

does not affect the princely states, where 93 million (25%) Indians live.

These are more or less despotically ruled by an anachronistic group of

princes who have, on the average, 11 titles, 5.8 wives, 12.6 children,

and 3.4 Rolls-Royces. Sooner or later a free Indian nation will have to deal

with them; right now the Communists are advocating expulsion of the

princes.

Power is the Spur. To bring under control this vast interplay of seemingly

irresistible forces and immovable bodies would take more than the

fanaticism of Moslem Leaguer Mohamed Ali Jinnah, more than Jawaharlal

Nehru’s eloquent idealism more, perhaps, than Gandhi’s combination of

mysticism and manipulation. India needed an organizer. It had one. Gandhi

listened to God and passed on his political ideas to Vallabhbhai (rhymes

with “I’ll have pie”) Patel; Patel, after listening to Gandhi, translated

those ideas into intensely practical politics.

Patel has no pretensions

to saintliness or eloquence or fanaticism. He is, in American terms, the

Political Boss…

As Home and Information Minister of the new Central

Government, as boss of the Congress Party, Patel

represents what cohesive power Free India has. This cinder-eyed schemer

is not the best, the worst, the wisest or the most typical of India’s

leaders, but he is the easiest to understand, and on him, more than on any

man, except Gandhi, depends India’s chance of surviving the gathering

storms.

Interrupted Rubber.

The first movement Patel ever organized was a student revolt against a teacher

he accused of profiteering in pencils and paper. Later, Patel went to London,

studied law 16 hours a day, topped the list in a bar examination and headed back

for his beloved India without stopping to tour the Continent. He has never left

India since.

His legal career was mainly defending murderers and bandits and

frightening district magistrates with his caustic tongue. One magistrate,

hearing that Patel was expanding his practice, moved his court to a town out of

Patel’s reach. In later years Gandhi found in Patel “motherly qualities” that

eyes less inspired than the Mahatma’s never saw….Enemies and friends tell an anecdote of his criminal law days. He had just put his wife in a Bombay

hospital, returned to Ahmedabad to argue a murder case. He was on his feet

when a telegram arrived. He read that his wife had died, put the

telegram into his pocket and went on with his argument as if he had

never been interrupted.

In 1915 Patel was playing bridge in Ahmedabad’s

Gujarat Club when he first saw his fellow lawyer Gandhi, fresh from

agitational triumphs in South Africa. At that time Patel dressed in fancy

Western clothes and affected the manners of the most pukka sahib Briton.

When his eyes fell upon Gandhi, Patel interrupted his game long enough

to make a few scathing remarks. A year later he joined Gandhi’s movement.

By 1927, when Patel had become the mayor of Ahmedabad,

unofficial capital of Gujarati-speaking India, his extraordinary skill as an organizer

showed itself for the first time during the great Gujarat floods.

Every-thing broke down – transport, communications, all methods of

distribution. The general Indian attitude used to be to regard such

catastrophes as acts of God. What little relief there was usually came from

a British Government which took its good time to relieve distress. Patel

initiated an unheard-of fund-raising drive for the relief of the flood victims.

Supplies were moved into the flood areas by hundreds of volunteers wading

through waist-deep water, carrying boxes and sacks on their heads. When lumber

was required for constructing small bridges or building houses, Patel arranged

for it all without making a single approach to the Government. It

seemed a miracle to Indians when all the lumber arrived on the scene in the

needed sizes. By the time the Bombay provincial representatives got there,

no official assistance was needed.

Nothing like it had ever been seen

before in India. Here at last was organization by and for Indians.

Somber Masterpiece. Now that India seems to require miracles of organization

if its Government is to survive, Indians recall Patel’s organizational

masterpiece, the Bardoli no-tax campaign of 1928. Despite the fact that

crops had been bad for several years in the Bardoli district, a 25% tax increase

was ordered by the Government assessors. This was precisely the

opportunity Gandhi had been waiting for to launch the first real

experiment in mass civil disobedience.

Patel took

charge. Dressed in simple dhoti and shirt, he trudged from village to village,

day after day, exhorting the peasants at every stop to stand fast and pay no taxes.

“Some of you are afraid your land will be confiscated,” he said in one

speech. “What is confiscation? Will they take away your lands to England?”

In another speech he set forth the principle that was to govern every

Congress struggle of the future: “Every home must be a Congress office and

every soul a Congress organization.” Under Patel’s orders the peasants’

buffaloes, which the Government might have taken, were brought right

into the peasants’ houses. No servants would work for the Government

collectors. Nobody would sell them food or give them water. Some property

was, of course, confiscated and sold, but bidders were few. In all Bardoli

not one rupee was collected in direct taxes.

A stunned Government

finally asked Gandhi for terms. The upshot was a 6¼%, not a 25% increase in

taxes. Patel emerged from Bardoli with a new and exalted status. He

received the unofficial title of “Sardar,” meaning captain or leader, which

he has carried ever since.

Money Makes the Mare Go. After Bardoli, Patel became recognized as the

Congress Party’s chief organizer and disciplinarian. He checked up on what

Gandhi’s followers ate, drank, and wore. He passed on the party lists in

provincial elections. He approved party-sponsored legislation, and personally

drafted much of it. No detail was too unimportant or sordid for Boss Patel.

Recently he took charge of negotiations between the Congress Party Ministry in

Bombay and the Western Indian Turf Association, which

wanted to renew its license for the Bombay racetrack. Patel, who has never

seen a horse race, knew what the traffic would bear. He upped the

license fee from half a million rupees to three million.

Although he has

handled millions in party funds, Patel has no personal love of money. With

his daughter Maniben, who acts as his secretary (she has accompanied

him on most of his sojourns in British prisons), he now lives in a little

suite in his son Dahyabhai’s Bombay house. He eats little, drinks no

alcohol, quit smoking when he first went to jail. In recent years he has

had serious stomach trouble. His only exercise is a walk when he rises, at

4:30 a.m. His only recreation is bouncing a ball across the room to his

grandchildren. He has never seen a movie. He cares little about the

world outside his country. Of 300 books in his Bombay library, every one

is by an Indian, mostly about India….

|